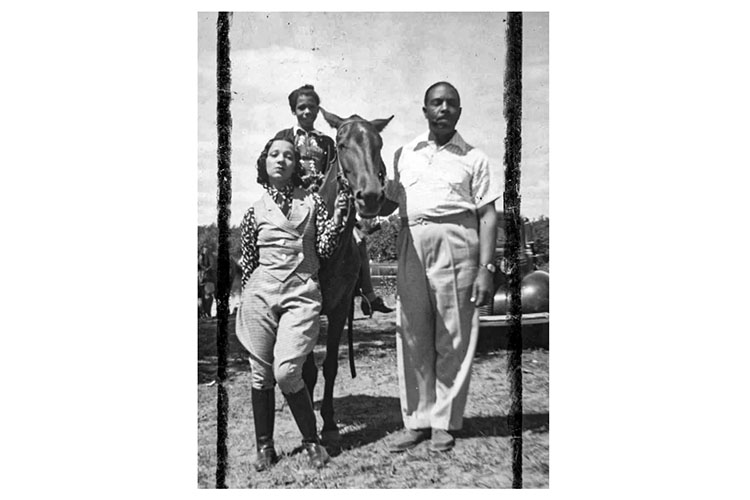

Idlewild, also known as "Black Eden"...was a resort town where Black people could feel safe, relax, and enjoy themselves during the decades of segregation across the United States. California also had a similar Black resort outside of Los Angeles in the city of Val Verde. Hattie McDaniel played a significant role in building the Olympic-sized swimming pool, and numerous legendary Black musicians performed in their grand ballroom while affluent Black individuals frequented this resort. We'll delve further into the history of Idlewild, often referred to as "Black Eden," shortly.

HISTORY OF IDLEWILD

Idlewild, an unincorporated community located within Yates Township in Michigan's northwestern Lower Peninsula, once thrived as a renowned Black resort town often referred to as "the Black Eden" during the majority of the first half of the 20th century. In the wake of the civil rights movement, numerous hotels, cottages, and clubs in the community have deteriorated. Nevertheless, there have been recent initiatives at both the state and local levels aimed at revitalizing this historic community. Despite its challenges, Idlewild continues to hold profound significance for many Black visitors.

"When you see the blinking lights at Broadway and US-10, you know you're in Idlewild and you get this feeling," says Ronald Stephens, a Purdue University professor who has written two books about Idlewild's history. "I don't know if it's totally psychological, if it's totally social or cultural or what it is, but you get this feeling of relief."

According to Stephens' research, when Idlewild was initially founded in 1912, it stood as only the third resort in America dedicated to serving Black visitors. During this period, segregation persisted in full force, severely limiting safe recreational options for Black families. Idlewild's establishment was the result of collaboration among a group of white developers, some hailing from Michigan and others from Chicago. They recognized an opportunity during what Stephens characterizes as "an era of upward mobility, a burgeoning Black middle class with access to education and disposable income."

"These developers weren't totally out for a profit for themselves," he says. "Although they were businessmen, they understood that there was a Black economy. They understood that there were Black intellectuals and professionals who, like white America, needed rest and relaxation."

While Idlewild was initially established by White individuals, it was swiftly molded and led by Black community members. Dr. Daniel Hale Williams, a notable Black surgeon renowned for conducting the first successful, documented pericardium surgery in the U.S., was one of the early property owners in Idlewild, purchasing land there in 1915. Williams retired to Idlewild and emerged as a significant landowner and community leader. He played a key role in co-founding the Idlewild Improvement Association, which acquired land from the white developers and later sold property to prominent Black figures such as W.E.B. DuBois and Madam C.J. Walker.

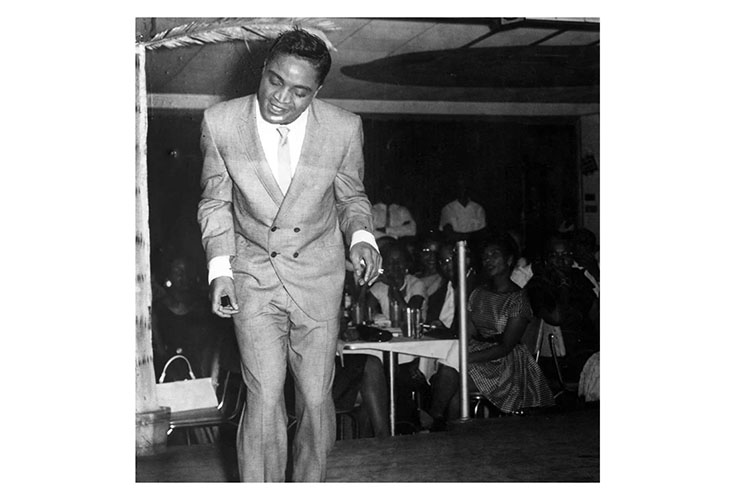

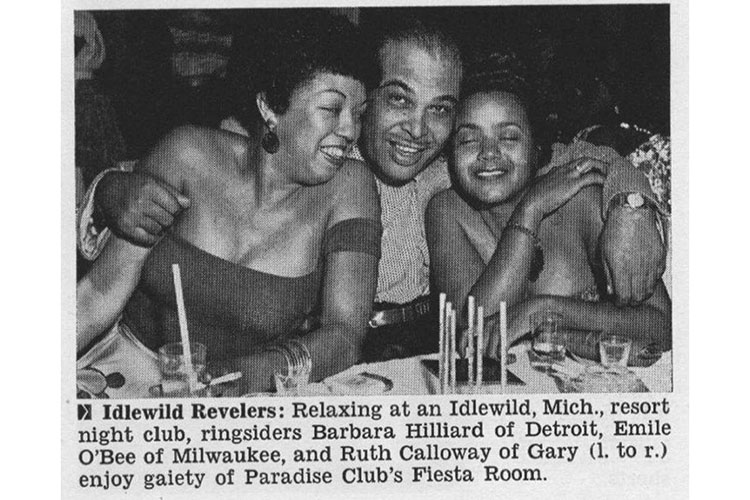

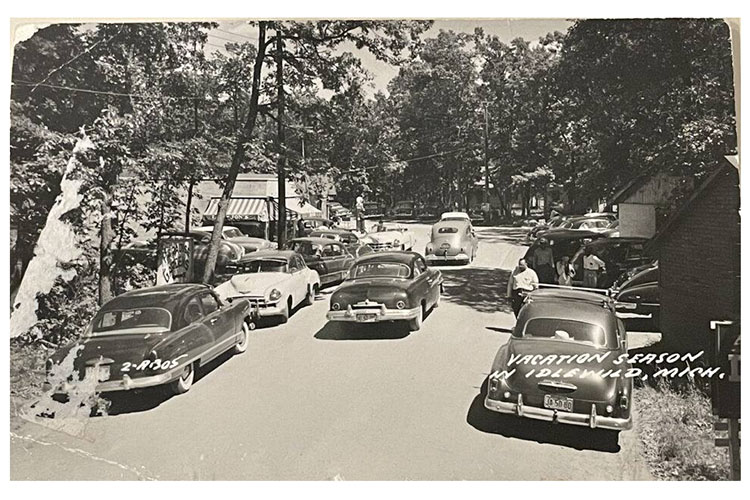

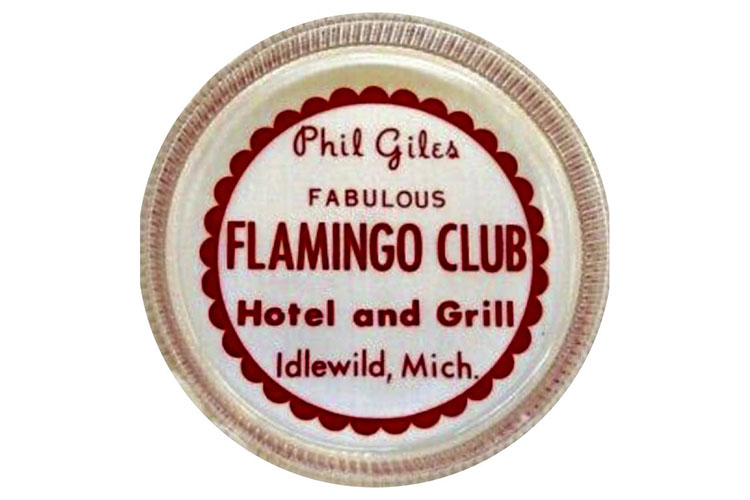

Stephens says the numbers of visitors, year-round residents, and developments "just kept growing and growing and growing" in Idlewild, even through the Great Depression, thanks largely to the publicity the community received through the Black press at the time. But Idlewild's biggest boom came after World War II, as the Detroit auto industry and America in general prospered. Idlewild became a major entertainment hub, hosting performances by Black megastars from Della Reese to Jackie Wilson to the Temptations to Aretha Franklin in the '50s and '60s.

"If you were a Black entertainer, you did Idlewild," Stephens says. "It was like how in the '60s, if you were to be recognized in entertainment, you had to be approved at the Apollo at Harlem. Well, the same dynamic happened in Idlewild."

In fact, Idlewild became known as "the Summer Apollo of Michigan." By the '50s, Stephens says, the community was "so packed" that it would draw 25,000 visitors in a given weekend. But as Black Americans entered a new era of advancement, the Black Eden would enter a new era of decline.

DOWNFALL

"The entrepreneurs in Idlewild were not prepared for what was happening," Stephens says. "They didn't truly understand what that meant, so they weren't reinvesting in Idlewild. Meanwhile, in Black America, something that had been denied...to go to another hotel, Howard Johnson or something, now these things are open to them. So to some degree, Black America abandoned its own institutions. That includes the consumer and the investor."

In the late '60s, Idlewild began to fall into disrepair, creating the near-ghost town that persists today.

"Things started slowly deteriorating," Stephens says. "People abandoned homes that had been inherited to them by not paying taxes. Businesses started shutting down or were torn down or burnt down. It was a whole other set of problems."

Idlewild indeed offered safety, relaxation, and a sense of community to Black Americans during its peak. However, it's important to recognize that the necessity for such a refuge arose due to racist federal and local policies. According to Stephens, Idlewild's existence can be attributed to the construct of segregation. The enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, while crucial milestones in the fight for civil rights, had unintended consequences for Idlewild. These legislative changes effectively spelled the end of Idlewild as a prominent destination because, suddenly, Black Americans were legally permitted to vacation anywhere they desired, and many of the newly available accommodations offered better conditions than those in Idlewild.

REVITALIZATION AND PRESERVATION

Many of Idlewild's buildings still remain unused or in a state of blight, but Stephens notes that he has observed a gradual revitalization taking place since his initial visit to the area in 1992. Yates Township maintains a population of 785, drawing tourists every summer. Moreover, local residents have collaborated with the state and other dedicated individuals to preserve and breathe new life into the community.

While this might be a bit controversial, it raises the question of whether Black communities, during the era of segregation, may have, in some ways, thrived economically because it compelled them to reinvest their money within their own communities. YES, segregation was heinous, but it does make you think looking at the state of Black America today. During this period, Black entrepreneurs successfully established various businesses, including hotels, resorts, markets, bed and breakfast establishments, theaters, Black-owned newspapers, boutiques, restaurants, and even the founder of the Green Book, which ensured safe travel for Black individuals across the nation. This forced interdependence led to the creation of substantial wealth within Black communities.

However, as with many businesses, such as the Idlewild resort, the end of segregation marked a significant shift. With newfound freedom to spend their money wherever they chose, Black individuals began to redirect their spending away from Black-owned businesses, and this loyalty to such establishments waned. Truthfully, the economic landscape has never fully returned to what it once was within many Black communities across the U.S.

#Idlewild #BlackEden #RonaldStephens #BlackResorts #segregation #Michigan #BlackEconomy #BlackFacts #MPJINews #secondwavemichigan